Validus appoints experienced infrastructure fund specialist

12 July 2023

Is the fight against inflation in North America nearly over?

19 July 2023INSIGHT • 12 JULY 2023

Bank of Japan: The Owner of Last Resort

Kambiz Kazemi, Chief Investment Officer

With the arrival of a new Governor of the Bank of Japan (BoJ) in April came a patient tone and an adoption of the status quo. The unchanged policy on Yield Curve Control (YCC) and interest rate levels has driven the yen lower, reaching the 145 level.

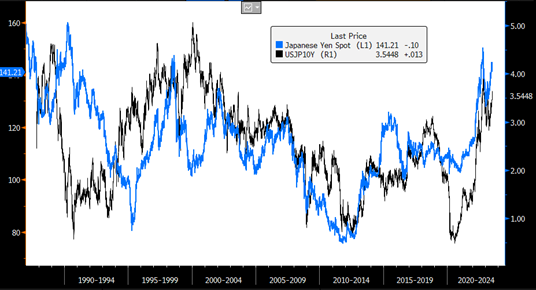

Despite core consumer price inflation (CPI) north of 4%, the BoJ is keeping overnight rates at the zero boundary and continues its targeting of the yield on 10-year Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) in the -/+0.50% band. As a result, the differential between the US and Japanese 10-year yields is once again at multi-decade highs making the carry trade even more attractive than the pre-2008 crisis period (borrowing low in Japan and getting paid high rates in US). While those involved in the carry trade in the early 2000s are believed to have been mainly foreign investors, anecdotal evidence points to the fact that recently Japanese investors might have also embraced the carry trade. Two main questions remain: where do things go from here? And what is the extent of underlying risk to the currency and bond markets if the BoJ changed its policy?

Chart 1: USDJPY spot and 10 year US-Japan rate differential

Source: Bloomberg

The Japanese government and central bank’s experimentation with easy monetary policy and fiscal stimulus is a much older story than many may think. In fact, it goes back to nearly 60 years before the bursting of the real-estate and stock market bubble in 1992.

When fiscal and monetary policies worked

From 1929 to 1931, the Japanese economy suffered a severe bout of deflation and depression (the Showa Depression) as a result of the Great Depression and its global impact. Interestingly, Takahashi Korekiyo, the Japanese Finance Minister (previously 7th Governor of the BoJ and one-time Prime Minister) implemented the “Takahashi Economic Policy” or Takahashi Zaisei, achieving high growth and some modest inflation. Core elements of his policies included:

- First, allowing the yen to depreciate by 60% versus the USD.

- Second, increasing fiscal expenditure backed by central bank credit,

- Third, having the BOJ conduct an accommodative monetary policy by cutting the official discount rate.

This combination of exchange rate policy, quantitative easing (QE) and easy monetary policy all done at once can arguably be qualified innovative and quite ahead of his time. It is similar to the policies adopted in the US during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 by Ben Bernanke and Henry M Paulson. Takahashi threw all the tools at his disposal at the deflationary crisis and was duly rewarded by a return of aggregate demand and some modest inflation in the following years.

However, by then the Japanese military was used to the fiscal largess resulting from the quasi-QE, and efforts to retore fiscal discipline (by cutting government spending) were not well received by a military keen to spend now that the economy was on sounder footing. Takahashi was assassinated in February 1936.

Will fiscal and monetary policies work?

While the Takahashi reforms bore fruit over a 4-year period, Japan’s more recent experiment with easy monetary policy and fiscal policy has lasted a few decades before some inflation has finally appeared, driven largely by external factors.

The magnitude of the policies adopted by Japan is astonishing by all measures. Total government debt as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew over three decades and stands at 260% (vs. 120% in the US) while the BoJ holds nearly half of outstanding JGBs.

However, in our close review of the BoJ balance sheet it is the YCC that stood out most and is admittedly astounding.

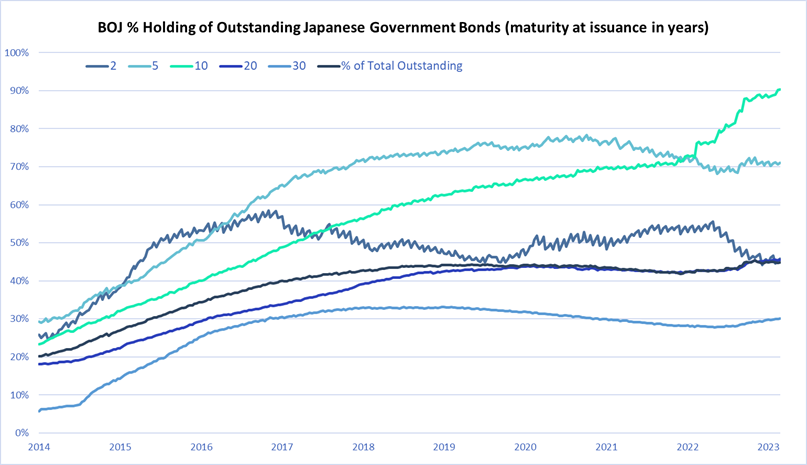

Chart 2: BOJ % Holding of Outstanding Japanese Government Bonds (maturity at issuance in years)

Source: Bank of Japan, Validus Calculations

Since its implementation– which targets the 10-year yield – the share of outstanding 10-year JGBs held by the BoJ of the total existing 10-year JGBs has increased from 70% to over 90%!

In other words, the BoJ owns nearly all 10-year bonds issued by the government of Japan. It has become de facto owner of last resort.

What could be the implications of this?

We therefore took a closer look at the BoJ’s holdings in order to determine what proportion of bonds which have 8 to 12 years remaining to maturity (the maturity the YCC program would focus on) was historically owned by the BoJ.

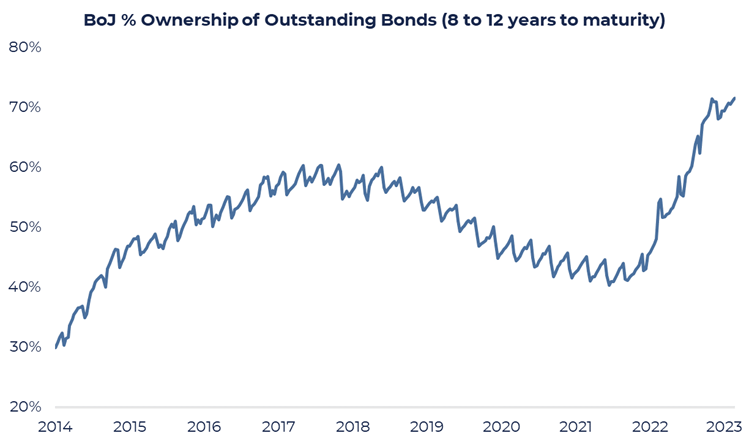

Chart 3: BOJ % Ownership of Outstanding Bonds (8-12 years of maturity)

Source: Bank of Japan, Validus Calculations

Once again, the data is unequivocal, the BoJ holds over 70% of the 8 to 12 years section of the yield curve, up from 40% in early 2022!

Paradoxically, for the time being, selling into the YCC program seems to have stabilized as:

- Many interested parties aggressively used the facility by selling into it from 2022 onward.

- II. There is also much less availability of bonds which could qualify for the selling facility.

Potential ramifications of this situation include:

- There is less liquidity available in that section of the curve – unless the BoJ decides to be a seller – and as such any changes in policy and major flows could result in noticeable price volatility, which in turn could propagate to other parts of the yield curve, in particular maturities close to 10 years.

- The market is “one way” with the owner of last resort holding over 2/3 of the market and being a buyer by design. This makes any decision by the BoJ to widen the band or end the YCC a very difficult one. With such a tilted market, any signaling by the only buyer at these levels of a reduction of its role embeds the risk of a sudden adjustment of rates higher which could trigger short covering by those involved in the carry trade (similar to the 2007/08 period), potentially igniting a feedback loop.

- A mitigating factor to this risk is that because yield differentials are so high between Japan and other developed markets, it will likely take an important rise in Japanese yields before the unwind of the carry trade is triggered.

All in all, it appears that due to its long-term accommodative policy the BoJ might find itself in a very difficult position, similar to a prisoner’s dilemma, should inflation continue to rise or stay at higher levels.

The BoJ might need to drive short-term and/or long-term rates higher to tame inflation. But such a move could present an important risk to the well-functioning of bond markets and have unintended consequences should it trigger the unwind of the carry trade.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.